As a Catholic, I oppose gay marriage with my whole being. But I also believe we lost the battle against it long before Massachusetts began issuing same-sex marriage licenses in 2004. Why? Because the real architects of gay marriage aren’t gay and lesbian activists, but Christians themselves.

Gay marriage actually began, ironically enough, with a call to sexual abstinence: in 1798, British (Anglican) clergyman Thomas Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population, the first work to advocate abstinence for population control. Forty years later, Charles Goodyear accidentally discovered how to vulcanize rubber and our old friend the condom was born. By the 1860s, Malthusians had officially dropped abstinence and promoted condoms for birth control.

Across the pond, Protestant Anthony Comstock saw the writing on the bedroom wall and successfully lobbied Congress to ban the sale and distribution of “obscene” material, including contraceptives. The Anglican bishops had their say, too—in 1908 and again in 1920, they emphatically reaffirmed the traditional Christian teaching against contraception.

Enter American birth control advocate Margaret Sanger, who worked with like-minded progressives in England to pressure public health officials and church leaders to accept contraception. Their lobbying worked and at the Lambeth Conference of 1930, the Anglican bishops caved and decided contraception was licit. The Episcopal Church of the United States joined them just a year later.

The response from the rest of the Protestant denominations, however, was fast and furious. Lutheran theologian Dr. Walter A. Maier called contraception “one of the most repugnant of modern aberrations,” and Methodist bishop Warren Chandler insisted that the “disgusting” contraception movement assumed the worst about man’s ability to control his sexual urges. The Presbyterian Church joined the chorus, openly calling for withdrawal of all interdenominational support for the Episcopal Church in the United States. But like all firestorms, this one burned out quickly. By the 1960s, every Protestant denomination—Lutheran, Methodist, Presbyterian, even the Baptists—had abandoned its opposition to contraception.

Most view the moral prohibition against contraception as one of those “Catholic things” that isn’t relevant to Protestant Christians, much less to non-Christians. For Protestants, at least, this not only ignores Christian tradition, but basic biblical morality. In the first two chapters of Genesis, God’s plan for marriage is laid out plainly, with God bringing man and woman together in marriage for two purposes: companionship (unity) and to grow the human family (procreation). This is why Protestants who oppose gay marriage because “God created them male and female” only have it half right. For God did not stop there; he joined the two together for specific purposes. In short, for bonding and for babies.

From the beginning of Christianity, what constituted a valid marriage was clear: a man and a woman, bonded for life, whose union is in service to new human life. But by 1960, contraception is okay and babies are optional. So now marriage is a man and a woman, bonded for life, whose union is in service to new human life.

Officially, the Catholic Church is the only Christian faith to have retained the traditional teaching against contraception. Unofficially, however, dissent–both institutional and among the laity–has been rampant. (Even today, the best litmus test I have for gauging the orthodoxy of a priest is his reaction to finding out I’m a natural family planning instructor.) While the official teaching of the Church remains unchanged, it was discarded by the majority of Catholics, who decided that the Church was wrong about contraception (but right about social justice and the rest of the teachings they agreed with). Even today, Catholics contracept and sterilize at the same rate as the rest of society.

Then came the push for no-fault divorce laws in the 1970s. And within a short time, couples that would have previously had to prove fault and undergo an arduous and agonizing court procedure to dissolve their marriage could now separate relatively easily, legally speaking. What had once been a last resort–divorce–was now considered a legitimate solution to the “problems” of marriage. And not surprisingly, the once-serious problems that had justified divorce in the past, such as abuse and infidelity, gave way to immature and self-centered reasons such as “I fell out of love with him” and “She no longer makes me happy.” Today, no one blinks an eye if someone wants to get married “for life” three, four, or more times.

Marriage, then, changed again: a man and a woman, bonded for life, whose union is in service to new human life.

Gay couples then, seeing that heterosexual marriage has become nothing more than a temporary legal contract between consenting adults, rightly asked why they couldn’t have their unions recognized, too. I sometimes cringe when I hear Christians talk about defending “traditional marriage.” Traditional marriage was open to children and until death. I can just hear the gay marriage advocates now: “So in the past 60 years, you’ve lopped off 2/3 of ‘traditional’ marriage, and now you want to claim it’s a sacred, unchangeable institution?”

They have a point, folks.

Logically, if heterosexuals–Christians, at that–have led the charge to so radically alter what makes a marriage a marriage, then what basis do we have for saying marriage must be reserved for just a man and a woman? We were the ones, after all, who fought to take procreation and permanence out of the equation. What’s left of traditional marriage is barely worth legally defending, which is why gay marriage has made so many inroads.

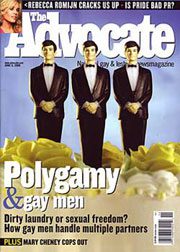

Polyamorist gay marriage: coming soon to a state near you. (June 14, 2006 issue of The Advocate, featuring an article about gay polygamists who expressed a desire to be legally married.)

After we’ve lost the battle for gay marriage, we’ll lose the battle for polygamy, too. Because if marriage is no longer a man and a woman, bonded for life, whose union is in service to new human life, but a temporary legal union of two adults, then why shouldn’t polygamists get their shot at the brass ring, too? Why should marriage be limited to just two people? What if three–or six–people want to get “married”? What reason could Christians–contracepting, divorcing, and remarrying Christians–possibly have to deny “polyamorists” the right to redefine marriage once again? We did, after all. Plenty of times.

My own faith is solid; I know what God intends marriage to be and I live that out with my husband. We’re open to life and prepared to stick it out until the bitter end. We teach these truths to our children, both through catechesis and example. But legally and socially, I believe we’ve already lost the battle against gay marriage, polygamy, and every other kind of “union” our crazy world comes up with for the government to ratify (“bestial marriage,” anyone?). With even most heterosexual marriages in this country being a mere shadow of what God intends this glorious institution to be, all we can do is hope for the best, prepare for the worst, and pray without ceasing that our own children will find the narrow gate to life.