“There are places in the heart that do not yet exist; suffering has to enter in for them to come to be.” – Leon Bloy

The past seven years have been, for the most part, hellish for my family. A member with chronic pain, the loss of two children, betrayals by extended family, crushing financial difficulties, the burgeoning special needs of our son, clinical depression, and finally, a lengthy employment separation of my husband from the family has left us feeling like the best we can do most days is tread water.

Throughout all this, there has been The Question, the one repeatedly whispered into my heart by God: “Do you trust me?” It’s the question that’s haunted humanity from the beginning, when Adam and Eve chose to shackle all of us to sin by answering, “No, we don’t.” In my own life, this is the question I hear each time the pain begins again, each time I’m faced with wondering why God has permitted this or that suffering into our lives.

In the movie, The Man Without a Face, Mel Gibson plays Justin McLeod, a disfigured recluse who helps a young boy, Chuck, prepare for boarding school. The two spend the summer together, becoming friends as McLeod trains the boy for the entrance exam. Then Chuck hears rumors that his teacher molested a former student. He asks McLeod point-blank: “Did you do it?”

McLeod: “Think Norstad, reason. Have I ever abused you? Did I ever lay a hand on you of anything but friendship on you? Could I? Could you imagine me ever doing so? And what about the past?”

Chuck: “Just tell me you didn’t do it, I’ll believe you.”

McLeod: “No, no sir! I didn’t spend all summer so you could cheat on this question.”

This conversation mirrors the one we have with God all our lives. We spend time in friendship with him, witness his incredible love and generosity toward us, and revel in that loving relationship. Then the suffering comes and like Chuck, we question whether God is really the all-loving, benevolent friend he seemed to be in the past.

Most of the time, we aren’t as direct as Chuck. We don’t say, “Just tell me, God, show me that you’re good one more time and I’ll believe you.” Instead, we pray for him to alleviate the suffering and when that doesn’t happen, we start to believe The Lie that felled Adam and Eve. We look around at others who appear to love God less, who haven’t been as faithful or long-suffering as we have. We wonder why the unbelievers and lukewarm seem to have escaped their allotment of earthly suffering when we’ve been given a double dose. We begin to doubt that God is all-good and that He loves us. Like a child, we resent the unfairness with which our Father appears to treat his children.

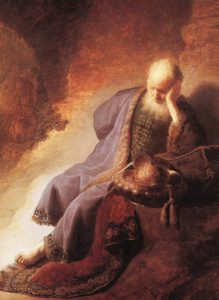

How many times have we wanted to ask, as Jeremiah did, “How could you do this to me, God? I trusted you!”

One thing I learned years ago when studying attachment disorders in children is that the more we love someone, the more deeply their capacity to wound us. If a stranger hits me, it hurts physically. If a friend hits me, it hurts physically and emotionally. But if my husband hits me, that’s the deepest cut, the one that causes lasting damage. (He doesn’t, just for the record.) This is why children with attachment disorders resist bonding with loving caregivers, because they don’t want to risk the awful pain of being hurt so deeply again. It’s not surprising, then, that we’re most wounded when we feel hurt by God, our most intimate friend. “O Lord, You have deceived me,” said Jeremiah the prophet, for all of us.

When we suffer, we’re offered two roads. The first, and most commonly taken road, is to interpret our suffering as proof that God’s promises are empty. He may love us, but that love is certainly not unconditional as we once believed. We experience what C.S. Lewis felt after his wife, Helen Joy, died just three years into their marriage:

Meanwhile, where is God? This is one of the most disquieting symptoms. When you are happy, so happy that you have no sense of needing Him, so happy that you are tempted to feel His claims upon you as an interruption, if you remember yourself and turn to Him with gratitude and praise, you will be–or so it feels–welcomed with open arms. But go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of bolting and double bolting on the inside. After that, silence. You may as well turn away. The longer you wait, the more emphatic the silence will become. There are no lights in the windows. It might be an empty house. Was it ever inhabited? It seemed so once. And that seeming was as strong as this. What can this mean? Why is He so present a commander in our time of prosperity and so very absent a help in time of trouble?

Not that I am (I think) in much danger of ceasing to believe in God. The real danger is of coming to believe such dreadful things about Him. The conclusion I dread is not ‘So there’s no God after all,’ but ‘So this is what God’s really like. Deceive yourself no longer.’

In our minds, that original image of God as a father who loves us unconditionally is gradually replaced by the fear he’s really just a “cosmic sadist,” to quote Lewis again. The doubt and resentment grow until we pull away from God, partly to protect ourselves from the pain of feeling betrayed again. We stop praying as often or praying at all. We start cutting corners spiritually, forgoing sacrifices and obligations we happily took on before. And maybe, underneath it all, we want to hurt Him a little, too. He made us hurt, after all.

The saints tell us over and over that suffering is a gift. That it’s the means by which God uses to purify us, to burn out the self-love that keeps us from a perfectly loving relationship with him. He accepts our meager suffering in this life as atonement for our sins, so we won’t suffer worse later in purgatory. He allows us to procure extra graces for those we love when we offer to suffer with Christ on the cross.

For most of us, though, it’s still hard to wrap our minds around the fact that suffering is a loving gift. After all, the people in this life who make us suffer rarely do so out of love. Even when we know, intellectually, that “all things work for the good of those who love God” (even and especially suffering), the notion of suffering being a gift just seems nonsensical in the midst of the fire. All we know is that we’re hurting and God is choosing not to take the hurt away, when we know He has the ability to.

Which brings us to the second road: choosing to believe that God is good and loving even when all the evidence points to the opposite. Choosing to believe that no matter how we feel, God does love us unconditionally and only permits the suffering we truly need to get to heaven. That his promises are as objectively true in suffering as they felt in good times. We can choose to believe that he is who he says he is: our loving father. A father who has an eternal perspective, not a temporal one, who allows us to experience the painful scalpel of suffering only because he knows it’s the only way we can heal from our brokenness and sin. And who’s willing to risk us hating him for it.

I’m convinced this is why God is so often silent in the midst of our heaviest crosses: He’s giving us the chance to answer the question of whether he can be trusted on our own. He lets us choose how to interpret our suffering, what road to take. And like the teacher in The Man Without a Face, he won’t let us cheat by giving us the answer during the test, because he knows we know the answer already.

Sometimes we’re blessed to see the reasons God permits us to suffer in this life, usually in hindsight. But most of the time, we’re not given the answers we so desperately desire. Suffering is the fork in the road that forces us to answer, “Do I trust God?” May we all have the courage to cling to God’s promises, even when circumstances and weakness cause us to doubt.