This past month I was fortunate enough to interview artist Daniel Mitsui. With stunning and unique Catholic artwork, Daniel is an artist to notice. His meticulously detailed ink drawings are made entirely by hand on paper or calfskin vellum and are held in collections worldwide. Since his baptism in 2004, most of his artwork has been religious in nature.

Daniel was kind enough to answer my questions and share a little more about himself and his art…

For starters, your art is stunning. I knew this when I asked for the interview. However, I didn’t expect to find such enlightening lectures on your website. They are a treat to read. I particularly liked your lecture titled Heavenly Outlook.

In light of that work, I was wondering if you could more generally comment on the differences between secular art and Catholic art. How should a faithful Catholic approach and appreciate art found both inside and outside of the church?

Thank you.

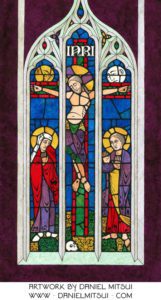

I do not think that art can be cleanly divided into categories of Catholic and secular. I think you need to consider at the very least three categories. First, there is sacred art that is used in the formal worship of the Church, or that is at least appropriate to be used there: musical settings of the Mass ordinary, vestments, stained glass windows, illuminated Psalters, things like that. Second, there is religious art that is about the Old and New Testaments, or the lives of the saints, or Catholic doctrines and morals – but is not really meant to reside inside the sanctuary. That includes things like Christmas carols and picture book illustrations. And then there is art that is not explicitly religious. But that art might very well present a religious worldview, or teach some important lesson, and thus still be considered Catholic art.

Although most of my drawings are commissioned or bought by individuals and used for private devotion, I try to uphold certain principles that would place them in the first category. What distinguishes sacred art is that tradition and beauty have a special, glorified meaning. I wrote in the lecture you mentioned:

To make art ever more beautiful is not to take it away from its source in history, but to take it back to its source in Heaven. Sacred art does not have a geographic or chronological center; it has, rather, two foci, like a planetary orbit. These correspond to tradition and beauty. One is the foot of the Cross; the other is the Garden of Eden. -“Heavenly Outlook” by Daniel Mitsui

So tradition is more than a matter of respecting old ways; it is about carrying Divine Revelation forward through history. Sacred art is akin to the sacred liturgy and the writings of the Church Fathers. It is one of the means by which the memory of what Jesus Christ said and did in the presence of His Apostles was  kept. For example, in sacred art, sacred liturgy and patristic exegesis, comparisons are constantly made between events of the Old Testament and events of the New Testament that they prefigure. This is not just poetic fancy; it is a way of thinking that Jesus Christ Himself taught: As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up.

kept. For example, in sacred art, sacred liturgy and patristic exegesis, comparisons are constantly made between events of the Old Testament and events of the New Testament that they prefigure. This is not just poetic fancy; it is a way of thinking that Jesus Christ Himself taught: As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up.

And beauty is more than a manner of pleasing the bodily senses. The appreciation of beautiful art and music is a vestige of our prelapsarian experience; it is a nostalgia for Paradise lost and a means of elevating our minds toward blessedness. Hugh of St. Victor, Suger of St. Denis and St. Hildegard of Bingen, three of the outstanding thinkers of the twelfth century, articulated this theology of beauty especially well.

In sacred art, both tradition and beauty are necessary. To neglect the former is to make sacred art into little more than a showy display.

To neglect the latter – to contend that so long as the art is traditional, it doesn’t really matter how beautiful it is – is a terrible diminution of its holy purpose. Very often, this is justified by a humbug idea of prayerfulness, an idea that to pray means to close your eyes and think pious thoughts to yourself, and nothing more. If this is the idea, then sacred art gets described as prayerful just for being easy to ignore. Any art that is especially beautiful, excellent, elaborate or interesting gets condemned as distracting because it actually compels you to open your eyes and ears and pay attention to it.

I really find this idea offensive. The backs of your eyelids are not windows into Heaven; they are mirrors back into your own imagination! Sacred art is supposed to lift you out of your own imagination, toward the spiritual realm.

Pulling from your lecture Invention and Exultation you are quoted saying, In our time, tradition is not a thing that is handed down so much as a thing that must be excavated. And once an artist begins to dig, he finds, in a different sense, altogether too much.

With this in mind, what do you think the contemporary Catholic artist’s role is in restoring or protecting the traditions of the faith? Do you think there are places for growth or renewal?

What I was trying to say in that lecture is that tradition has an objective content, a content that anyone can discover. Elsewhere, I have written:

It is an all-too-common error for the faithful in the present day to confuse tradition itself with its legal enforcement by ecclesiastical authority- as though tradition were nothing more than a stack of documents bearing the correct signatures. This is an epistemological absurdity; the bishops who are tasked with writing these documents need to know what they know somehow! –“Heavenly Outlook” by Daniel Mitsui

A pope or bishop has no privy religious knowledge that is hidden from the rest of us. Insofar as he knows what is actually traditional, he knows it the same way that you or I do: based on evidence in the agreement of the Church Fathers, the law of worship and the ancient, universal practice of the faithful. The necessary keys to understanding it are the gifts of the Holy Ghost received at Baptism and Confirmation.

I think that a many of the Catholic faithful who are frustrated by bad art, bad music and bad architecture in their churches see no way to fix the problem except by having a pope or bishop write and sign and enforce a document condemning it. I don’t expect any such document to be forthcoming. If I did, I honestly would be terrified. A magisterial attempt to regulate sacred art can do far more to impede the creation of good artwork than bad. I am remembering especially the ruinous efforts of the bishop John Molaus in the late 16th century.

I think that a many of the Catholic faithful who are frustrated by bad art, bad music and bad architecture in their churches see no way to fix the problem except by having a pope or bishop write and sign and enforce a document condemning it. I don’t expect any such document to be forthcoming. If I did, I honestly would be terrified. A magisterial attempt to regulate sacred art can do far more to impede the creation of good artwork than bad. I am remembering especially the ruinous efforts of the bishop John Molaus in the late 16th century.

Hopefully, more and more of the faithful will realize that they do not need to wait for official permission to discover, preserve and restore what is actually traditional, or to make beautiful artwork that honors it – whether contributing as artists or patrons. Sacred art is one of the few endeavors that the Church has entrusted to laymen for a very long time, and that is today an advantage.

Your art is incredibly complex and detailed. What is your process? What tools do you use? How do choose the different symbolic pieces for your overall composition?

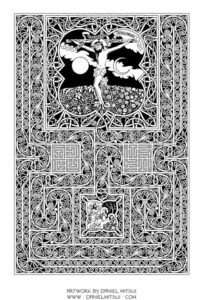

My preferred medium is ink drawing on calfskin vellum. I do not usually make rough drafts. I work out a composition in pencil on calfskin, then ink over the outlines using a metal-tipped dip pen. I use the pen to apply dark colors, and then paintbrushes to apply light ones. A knife is useful both for correcting mistakes and scratching additional details into the ink once it is dry.

Because calfskin is translucent, I sometimes draw details on the opposite side, in reverse; these can be seen faintly through the vellum, or more clearly when the drawing is held up to a light. Thus, the drawing has a different character depending on the angle and time of day that it is seen.

As for figuring out the appropriate symbolism, that is mostly a matter of preliminary research – into patristic commentaries, art historical writings and older works of art. A useful reference is the Biblia Pauperum, a book from the late Middle Ages that presents forty events from the life of Jesus Christ, each juxtaposed with two events in the Old Testament that prefigure it, and four prophecies.

Admittedly, I am quite a novice when it comes to appreciating and understanding both the devotional purposes of Catholic art and the regularly occurring symbolism that can be found around a church. Where should beginners start? Are there any resources you would suggest?

Some of the very best books for an introduction to the symbolism in sacred art are the trilogy written by the French art historian Emile Mâle, Religious Art in France of the Middle Ages. There is one volume on the 12th century, one on the 13th, and one on the late Middle Ages. All of these have been translated into English. The volume on the 13th century, sometimes titled The Gothic Image, is the most comprehensive, and the easiest to acquire. It has its flaws, but it holds up remarkably well for a scholarly work written a century ago. Another very valuable resource is The Golden Legend, a collection of saints’ lives and commentaries on liturgical feasts that was compiled in the 13th century by Blessed James of Voragine. An English translation by William Granger Ryan is in print.

Full transparency, I am a huge fan of your rosary coloring book. I have often used it as part of my own devotional practice. I am excited to share it with my children in the coming year. As a father, what is your advice when it comes to exposing children to Catholic art?

My purpose in teaching my children about art is not for them to appreciate art just so that they can one day sound smart talking about it! I rather want them to think of it as an ordinary and necessary part of their lives and something that they can themselves make. So in my home, we present holy pictures as familiar things: my kids kiss them goodnight and carry them in household processions. We place pictures around the yard for a little pilgrimage on All Saints’ Day; we hide a handwritten Alleluia sign before Septuagesima; we cover the statues with cloth during Passiontide.

My publisher is marketing my three coloring books (Mysteries of the Rosary, The Saints, and Christian Labyrinths) to adults, but I always thought of them as being for children also. My four kids all love to draw, and don’t need any special encouragement; but for kids who are less inclined, coloring books can be a way to encourage them to participate in art at an early age.

My publisher is marketing my three coloring books (Mysteries of the Rosary, The Saints, and Christian Labyrinths) to adults, but I always thought of them as being for children also. My four kids all love to draw, and don’t need any special encouragement; but for kids who are less inclined, coloring books can be a way to encourage them to participate in art at an early age.

A lot of coloring books marketed to children, especially religious ones, have really insipid artwork and that, of course, defeats the whole purpose. Children appreciate artwork that is made with care and detail; they don’t actually want to look at things that look like they were drawn by other children! I hope to offer an alternative, both with my coloring books and the individual coloring pages available for download on my website,

I advise parents to keep an eye out for picture books on religious subjects that have especially fine illustrations, ones influenced by manuscript illumination or other traditional sacred art. Some favorites in our home include Mikhail Fiodorov’s Bible Stories, Maurice Boutet de Monvel’s Joan of Arc, Heidi Holder’s The Lord’s Prayer, Pamela Dalton’s The Story of Christmas, Barry Moser’s Moses, Tomie de Paola’s St. Francis and Gennady Spirin’s Creation. I care more about my children appreciating these illustrations and copying them than about their knowing the big famous names of art history.

Where can people connect with you?

My website is www.danielmitsui.com. This is where I display recent drawings, prints, and writings. I have accounts (Daniel Mitsui, Artist) on Facebook and Pinterest, and my e-mail is danielmitsuiartist@gmail.com. I am accepting commissions now.